On a scorching summer afternoon, David Taylor Sr. stands under a tent in his hometown of Buckhannon, West Virginia. He is dressed formally -- his tie, accented with stars and stripes.

Before him, two Marines fold the flag 13 times, as is Honor Guard protocol. As the clouds break, Taylor links arms with his family. The summer rain pings off the red tarpaulin, almost masking the soundtrack of their collective anguish.

They desperately miss their “Bubbie.”

David Taylor II was only 25 when his life ended on the battlefields of Syria.

David Taylor II

Less than a month later, on Labor Day, it is another family’s turn to grieve. They are in a place far from the open fields and trees of Buckhannon’s Jawbone Park.

Robert Grodt’s family gather at Theatre 80, an off-Broadway space in New York’s East Village. Inside are a scattering of left-leaning activists wearing photos of a young man on their lapels.

Grodt, too, was killed in Syria. He was 28.

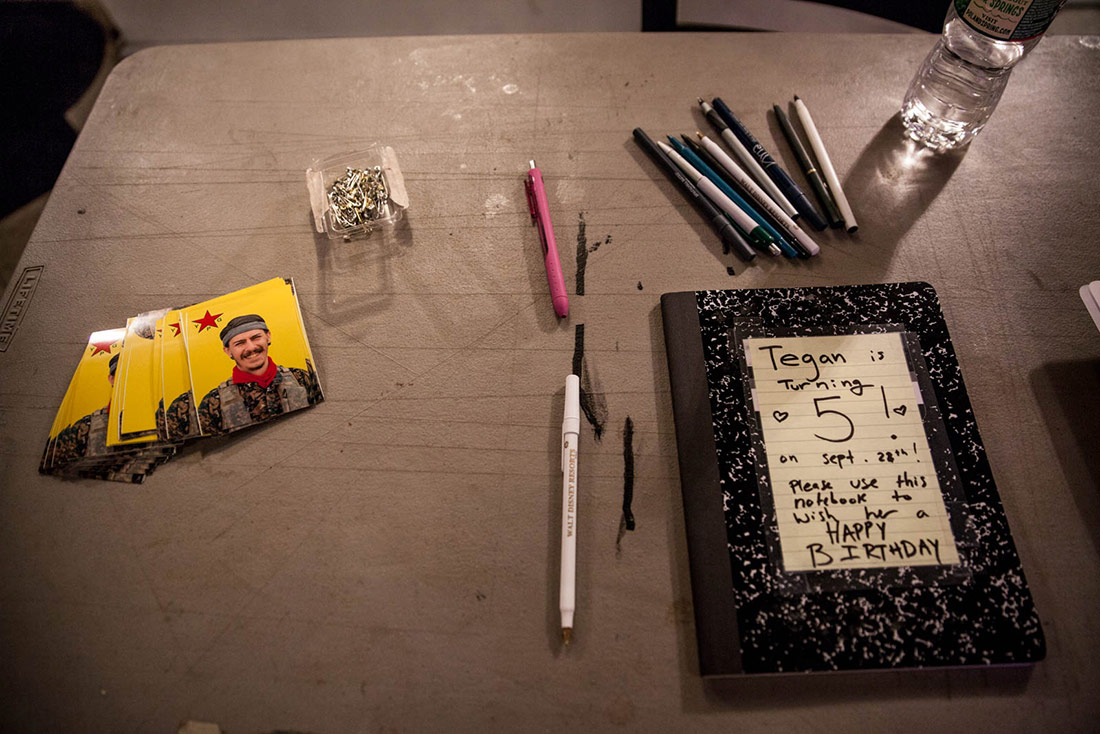

His four-year-old daughter, Tegan, runs circles around strangers who sign a book placed in the lobby by her mother. Tegan knows her father won’t be there for her upcoming fifth birthday; that he is never coming back. But she’s not talking about it much. It’s all too fresh.

Taylor and Grodt came from disparate backgrounds.

One was a Marine whose captain considered him reliable enough to be his personal alarm clock. The other had hitchhiked across the country to join Occupy Wall Street protesters in New York’s Zuccotti Park.

Robert Grodt

Both were leading comfortable lives in America until they felt compelled to risk all for their beliefs.

The two were chasing separate versions of the same dream: one that married American values of freedom, equality and justice with the fight against ISIS on the dusty plains of Syria.

Taylor and Grodt were among an estimated several hundred foreign volunteers who, for different reasons, dropped everything to fight for a Kurdish militia thousands of miles from home.

They were killed in July, within two weeks of one another, in separate bomb blasts in Raqqa, the city that was an ISIS stronghold until it fell in October.

The Taylor and Grodt families were once strangers, but in shared grief they’ve found one another online, keeping in contact ever since. They are connected by a desire to make sense of their sorrow -- and the drive to bring justice to memories of their loved ones lives lost too soon.

Framed by a blue sky, a newly printed banner containing David Taylor II’s Marine headshot flutters in a momentary breeze. Attached at the bottom is a black piece of fabric with the words: “Killed in Action. Raqqa, Syria.”

Taylor’s father had come up with the idea to transform the entrance of Jawbone Park into a “walk of valor,” a canopy of banners honoring the town’s fallen soldiers. He never imagined that one day it would become this personal.

The banners are now a backdrop to his son’s service.

An Upshur County Honor Guard salutes veterans and service members as the ceremony begins.

Patriot Guard riders flank the park's perimeter. “We stand for the fallen, we stand those who stood for us,” ride Captain Wayne Turner says.

Taylor’s family heads toward reserved chairs under a tent while friends trickle in. They pause to find the right seat long the open-air corridor. Many are from Buckhannon, a tight-knit West Virginian community of 5,612 people. Others have driven hundreds of miles from Florida, New York and the nation’s capital.

The guests approach the family, comforting them with stories about Bubbie. The words “brave” and “freedom” are never far from their lips.

Beneath the banners, a photo slideshow plays curated memories on a screen near the podium.

David Taylor Sr. spent weeks meticulously planning the service he calls a celebration of his son's life.

The crowd mourns.

The Honor Guard prepare a rifle salute.

We see Bubbie in diapers, dwarfed by a guitar in his lap; a blond child blowing out six candles on a chocolate birthday cake; a young man drinking beer at a baseball game; a clean shaven, uniformed Marine hugging his grandmother; a bearded volunteer fighter in camouflage fatigues adorned with the tricolored patch of the YPG, the acronym for the People’s Protection Units, the US-backed Kurdish militia leading the fighting against ISIS.

In 2014, the YPG ran a daring campaign to rescue Iraq’s minority Yazidis from impending genocide at the hands of ISIS. That victory catapulted the YPG into the international spotlight, bringing attention to a well crafted social media campaign that helped to recruit foreign fighters like Taylor.

The YPG offers former service personnel the chance to fight ISIS on the ground without constriction -- and dreamers the chance to rebuild a new society in northern Syria. Taylor was trained as a soldier, driven by a vision for humanity.

His service has the trimmings of a military funeral and the mourners know the drill. Patriot guards hold supersized flags. Musicians perform James Taylor’s West Virginia tribute, “Country Road.” An evangelical preacher’s words rise and fall as baseball caps are removed and eyes, lowered.

Taylor's mother, Becky is given a Bible by the Upshur County Honor Guard.

Taylor’s former Marine captain takes the stage to speak of Taylor’s dedication during his four years of service and the qualities that made him unique. “Who brings Shakespeare to war?” he says of the avid reader, who loved classical literature, poetry and music.

Special guests stand at the podium as a recorded tribute to Taylor II's mother plays over the loudspeaker.

Nearly 500 banners hang in the park's Wall of Valor. Taylor II's is the most recently printed.

Taylor best friend, Alex Cintron, delivers a soliloquy as circuitous and deep as the story of Taylor’s journey to Syria.

“When David was in the service he saw the atrocities that took place,” Cintron tells the crowd.

“And he said to himself: ‘You know these aren’t Syrian problems, they’re not Middle Eastern problems, they’re not Muslim problems, they’re human problems. They are people problems and if I have the power and the knowledge and the ability to do something, then damn it, I have the responsibility to do something about it."

“So he did it. Selflessly, courageously.”

Taylor’s family nod in silence. This was the Bubbie they knew.

The clouds open as the service concludes with a flag folding ceremony.

The man who they knew less was Zafer Qerecox, Taylor’s nom de guerre that translates to “Victory of Qerecox,” the YPG’s headquarters.

Representatives of the YPG and the Kurdish American community have traveled far for Taylor’s service. There is even a man calling in from Raqqa.

Nuri Mahmud, a YPG officer speaks of Taylor’s service, dedication and the quest for freedom against a common enemy. It’s a story that feels familiar to a crowd filled with American veterans and his words bring an once distant war home to small-town West Virginia. The reasons why Taylor risked it all becomes very real.

Ozlem (left), a member of the North American Kurdish community comforts Taylor's sisters Katie and Lauren (center). "We are now your sisters too," she says.

Many locals attend the service, including some Boy Scouts.

The ceremony celebrates a life lost. But it does not fully explain why a young American felt a calling. As the guests begin leaving, Taylor’s parents tell me about their son’s 10-month tour of Afghanistan.

“The behavioral changes in him were significant. We knew that the impact of war had taken its toll,” Taylor’s father says.

His son’s discharge papers pointed to post-traumatic stress syndrome and the trouble he had re-adjusting to civilian life. Taylor was unable to erase the horrors of suffering he had witnessed, yearning for an opportunity to right some of the wrongs in the world.

Taylor's family visit the Reed Cemetery, where his VA headstone would be placed.

He saw that opportunity with the YPG.

When the Arab Spring swept the region in 2011, Kurds living in northern Syria started a revolution of their own in a region known as Rojava. They called for democracy, equal representation of the sexes and a cooperative-based economy.

Taylor found the YPG’s commitment to women’s rights and the environment more in line with his worldview. Enlisting with the militia, he thought, would be a more efficient way of tackling terrorism.

Alex Cintron (right) speaks with Taylor's close friends at an informal gathering after the service.

Over late night drinks last December, Taylor confided in his best friend Cintron.

Then he embarked on a trip across America, spending time with his family in Florida and West Virginia before setting off on what everyone thought was a European road trip, but now realize was a good-bye tour.

Cintron hugs Becky Taylor, David Taylor II's mother.

“The YPG allowed him to be himself more than the Marine Corps,” Cintron says.

Thu, May 18, 02:09

Hey dad it’s David, I’m using a friends phone right now. I haven’t had internet for a while. Im in northern syria now with YPG doing the whole fight ISIS thing. I’ll be back by Christmas. Dont tell anyone where I am and dont put anything online. Love you and ill email you when I can.

David

David

Thu, May 18 06:51

Hey Bubbie ---- I love you……please be careful and I can not wait for you to get home……I won’t post anything at all…..proud of you 1000%

Do you want your mama and papaw to know. She calls every few weeks wanting to know where you are and what you are doing

Did the Corps call you back? How did this come about….

Do you want your mama and papaw to know. She calls every few weeks wanting to know where you are and what you are doing

Did the Corps call you back? How did this come about….

Thu, May 18, 08:29

Hey pops you can let them know just make sure they know to keep it to themselves. The sisters as well. Usmc didnt call me back just decided to volunteer because it’s the right thing to do. The US is arming the kurds now so we’ll have support. The YPG is a kurdish military that accepts foreign volunteers. Love you too!

Ok. I just spent the last 2+ hours reading everything I can online from credible sites about YPG. PLEASE send me notes when you can so I know you are ok. I just read that the US will be backing them more than they have in the past! PLEASE come home at first opportunity but while you are there stay as safe as possible !!! I’ll worry about you 24/7 until you are back home with us. Love you Bubbie!!!

Ok.

Text messages between Taylorand his father.

It’s not illegal for US citizens to join the YPG, but the group’s international standing complicates matters. The YPG and the US are allies in the ground war in Syria, with the YPG providing the bulk of the ground forces that have driven ISIS out of northern Syria. But they’re seen by Turkey, a NATO ally, as an arm of a designated terrorist organization that threatens Turkish sovereignty.

For those reasons, and for the simple danger in fighting alone, volunteers often don’t openly talk about their plans. They know that friends, families and even the US State Department might dissuade them from walking into the throes of war without any formal governmental protection or backing. They also know ISIS militants have placed bounties of up to $160,000 on their heads.

Taylor’s father shows me the first text message he received from his son in Syria. He told his dad not to worry and that he would be home by Christmas.

“The US is arming the Kurds now so we’ll have support,” the younger Taylor wrote.

The morning after the memorial, Taylor’s family and friends hike up to the family farm in the foothills of the Appalachians.

Taylor’s father walks through the overgrown grass, speckled with small purple flowers and yellow bees.

The lyrics to Taylor II's song, "The Farm" read: "Will you take me back, back to the farm / To the place where things were easiest / Will you take me back to the fields of green to the mountain streams / I wish you could take me back"

His son was like a butterfly, he thinks. David would go somewhere and land for a bit, flutter away and find another place to land.

But no matter what, he’d always found his way back home. This time was different.

It’s late afternoon and the sun casts shadows over four generations of women navigating their way to a New York memorial. On a public holiday the traffic is less than usual.

Labor Days seems a fitting time to honor a man who worked to help improve the lives of the needy.

Robert Grodt was always in search of a cause, his mother, Tammy, tells me. He needed something to devote his energy to.

Martha Dedrick (left) and Tammy Grodt, Rob's mother, hold their granddaughter Tegan's hand as they cross over 1st Avenue in Manhattan.

She arrives at a downtown performance space founded by early 20th century activists who also supported a militia of Americans that fought fascism in Spain. That significance isn’t lost on Grodt’s family.

Grodt is greeted by a handful of Kurdish independence activists. I recognize a few faces, including two American YPG volunteers who had travelled the month before to West Virginia for David Taylor's funeral.

Tammy Grodt holds the hand of her granddaughter Tegan, who has the same brown eyes and porcelain skin of her father. Many of the mourners today are keen to meet her. One man calls her a “child of the revolution.”

Not one to be coddled by strangers, Tegan runs inside the dark theater, where a handful of people are bustling around the stage. They look like they could be preparing the set for a Broadway play. Two men in red, yellow and green checkered scarves tape a banner to a wall of exposed brick. It reads: "Smash Patriarchy, Destroy Sexism, Support YPG.” Next to it is the Antifa flag, a symbol of the Anti Fascist movement.

Activists put the finishing touches on the stage before the memorial begins.

Grodt's grandmother Regina Steffani (left) and mother Tammy pin Robert's official YPG photo to their shirts.

Robert Grodt’s official YPG photo graces the stage on an artist’s stand. He is wearing military fatigues trimmed with the red scarf of a revolutionary. And he’s smiling.

The scene laid out in front of us is seemingly a world apart from David Taylor’s southern funeral. But as the service begins, I can’t help but think that these strikingly different men had drawn from the same well of American optimism; that with dedication and fortitude, they could make the world a better place.

Over the next two hours, Grodt’s life unfolds through the words of friends and family. Activists around the world are watching a livestream of the service. So are David Taylor’s relatives – the two families forever bound by shared heartache.

Robert and Kaylee's daughter, Tegan Grodt.

Grodt grew up in southern California with activism in his veins. When he learned about AIDS, he wanted to find the cure. He dreamed of rescuing pit bulls and even did some work with the ACLU.

Then, in the fall of 2011, the Occupy Wall Street movement was taking off and Grodt hitchhiked across the country to join the group as a volunteer medic. He raised funds along the way to donate to what eventually became the food canteen for protesters camped out in Zuccotti Park.

One night, Grodt came to the aid of fellow demonstrator Kaylee Dedrick after she was pepper-sprayed by police and became an image of the movement.

“We fell in love at first sight,” Dedrick recalls. “Well, he saw me first and because I was pepper sprayed, I didn’t see him till later."

Kaylee Dedrick is comforted by her father, Charles, as she remembers her partner Rob.

The couple moved to upstate New York and started life as a family. Tegan was born in September 2012, prompting many activists to hail her arrival as a physical manifestation of the movement.

On the screen now are images of that life: Tegan sitting on her father’s lap on the plane ride to Disney World; Grodt fixing the wheel of her stroller; smiling selfies of the young couple. The soundtrack of the videos is as emotive as the images: a revolutionary song of a female Kurdish fighter.

Grodt learned about the Kurdish independence movement online in between his job at a grocery store, potty training and reading to his daughter -- “The ABC’s of Anarchy” was her first book. He never lost interest in social activism.

A book to wish Tegan a happy birthday sits on the table inside the theater. Tegan is about to turn five and it will be the first without her father.

Kaylee Dedrick’s mother Martha: “Our hope is in his death, as awful as it is for us, that maybe dialogue will change. Maybe in his death he will accomplish something just as great as if he would have lived.”

He, like Taylor, was also inspired by the Kurdish Rojava project. It appeared a bastion of hope and a peaceful way to rebuild war-ravaged Syria.

Grodt’s journey, like most, started with a message online and a questionnaire intended to weed out “psychopaths,” Anthony Delgado, another American volunteer and former Marine who fought alongside Grodt, tells me.

Grodt had taken the Kurdish name of Demhat Goldman. At the memorial, a YPG officer in Raqqa calls him a martyr, a man who is destined to be canonized in children’s books on the revolution. Some in the audience clench their fists and chant: “Sehid Namirin!” Martyrs never die.

Grodt’s family had never thought of their son in this way. He had no military training, after all. The closest he came to combat experience, they joked, was playing Minecraft or paintball. Nor had he ever traveled to that part of the world.

But last Christmas, Grodt told Dedrick and his parents that he was joining the YPG. They knew better than to convince him otherwise. That would only push him out the door faster.

Feb 28th, 10:42AM

When are you coming home?

i mean atm looks like im home in august?

It could be sooner but that is only if I feel I need to leave sooner

It could be sooner but that is only if I feel I need to leave sooner

Not seeing any good news – looks like support isn’t there or at least switching sides. Kinda hard to even have a clue the way everything is all mixed up here (fake news, alternative facts) Just being “mom” – sorry.

honestly some pretty encouraging news came out today

the US has placed troops on the ground between the turks leaving al bob and the SDF controlled manbij

the US has placed troops on the ground between the turks leaving al bob and the SDF controlled manbij

if turkey does try to retake manbij depending on how things develop from that I might make plans for early departure

ive only gotten 3 hours of sleep since I left CA so ima catch up on that.

i love you mom

i love you mom

Apr 19th, 12:00 PM

all is okay im in serkani in northern Syria the internet thing will be sorted soon. Please relax Ma all will be fine

Text messages between Grodtand his mother.

By February, Grodt was boarding a plane to Iraq.

Delgado, a former Marine, remembers seeing Grodt and thinking that he was “hippyish” looking. But he was wearing desert boots, a sure sign of an American heading to that part of the world.

Grodt spent days in a safe house, after which he walked under the cover of night for seven hours into Syria.

“I couldn’t fathom why other people would want to be there, but I had learned quick from Rob that he was there for the ‘revolution,’” Delgado tells me. “I’m like, ‘what revolution, what does that mean?’”

Grodt’s family didn’t initially know much about Rojava. But they inherently knew their Rob was a soldier of solidarity and understood the causes he was fighting for: education, equality and democracy.

He wanted to shape Rojava, they learned, but he also wanted to make the world a safer place for his daughter and all children.

"He died defending the people of the land, he loved them,” Grodt's mother Tammy says.

Members of the Kurdish community offer their condolences to Grodt's family.

Kaylee Dedrick reveals her new tattoo: a YPG flag with the words "Sehid Namirin," Kurdish for "martyrs never die," inked below her partner's nom de guerre.

Grodt died July 6 from a blast in Raqqa, 10 days before Taylor. Three months after their deaths, US-backed coalition forces declared the city retaken from ISIS.

One of the American foreign volunteers who I meet at both funerals tells me he is thinking of returning to Raqqa soon. This time, it will be not to fight but to fulfill Grodt’s dream of rebuilding, spelled out in the promise of his Kurdish name Demhat, which means “the time has come.”

It’s a dream that Kaylee Dedrick still believes in. She now sports a newly inked tattoo of the YPG flag on her upper left arm that peeks through her sleeve as she stands to speak.

“I miss my partner but he’s left behind a legacy and no one will forget his name. Robert Grodt, Sehid Demhat, my hero.”

There is no bugler or honor guard at Grodt’s memorial. Just friends and family, who now step outside onto a New York street and light up cigarettes under a near full moon, lamenting the loss of their American dreamer.

Unknown Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetuer adipiscing elit, sed diam nonummy nibh euismod tincidunt ut laoreet dolore magna aliquam erat volutpat.

Labels

#End SAR

(1)

#End SARS

(5)

2019

(1)

9/11

(1)

Abacha Loot

(1)

Abuja

(1)

Accident

(3)

Adewunmi

(1)

AfDB

(1)

Afghanistan

(2)

Africa

(6)

African Culture

(1)

Agriculture

(1)

Aisha Buhari

(1)

Ajunwa

(1)

Akwa Ibom

(1)

Anglophone

(1)

Anita Joseph

(1)

APC

(1)

Argentina

(1)

Art

(3)

Article

(24)

Assault

(1)

AU

(2)

Australia

(1)

Australia Parliament

(1)

Babies

(1)

Banking

(1)

Barrack Obama

(1)

Bayelsa

(1)

Bayelsa State

(1)

Bayern Vs PSG

(1)

BBC

(1)

Bello

(1)

Benue State

(4)

Bitcoin

(4)

Bobrisky

(1)

Bokoharam

(1)

Bombing

(1)

Bosnia

(1)

Brazil

(1)

Brexit

(3)

Britain

(1)

BudgIT

(1)

Buhari

(6)

Burna Boy

(1)

Business

(2)

Cameroon

(2)

Catalonia

(1)

CBN

(1)

Champions League Draw

(1)

Charlyboy

(1)

Child Abuse

(1)

Child Rape

(2)

Chile

(1)

China

(9)

China.

(1)

Christmas

(1)

Christmas 🌲

(1)

Cocktail

(1)

Commits Suicide

(1)

Corruption

(2)

Cote d'Ivoire

(1)

Coup

(1)

CPS

(1)

Crime

(5)

Cure

(1)

Cyprus

(1)

Czech Republic

(1)

Daddy Freeze

(3)

Daura

(1)

David

(1)

Disco

(1)

Documentary

(1)

Domestic Violence

(1)

Dr Chris Ngige

(1)

Earthquake

(2)

Economy

(14)

ECOWAS

(1)

EDUCATION

(8)

EFCC

(3)

Eid el-Malud

(1)

Ekiti

(1)

Ekiti State

(3)

Election

(7)

Entertainment

(9)

Enugu

(1)

EU

(3)

Europe

(1)

Export

(1)

Extra- judicial killing

(1)

Fashion

(3)

Fayose

(1)

FBI

(1)

FCSC

(1)

FEC

(1)

Federal Government

(3)

Fela

(1)

FETO

(1)

FIFA

(1)

Fire Accident

(1)

Florida

(1)

Floyd Mayweather

(1)

Food Recipe

(1)

Food Recipes

(3)

Football

(1)

Football News

(2)

France

(1)

Fraud

(2)

FRSC

(1)

Fuel Scarcity

(1)

Fulani Herdsmen

(7)

Fun

(3)

Future Awards Africa Winners

(1)

G- Worldwide

(1)

Gay

(1)

Gaza

(1)

Germany

(5)

Ghana

(1)

Gist

(1)

Gossip

(55)

Gossips

(1)

Guinness World Record

(1)

Hamas

(1)

Health

(50)

Highlight

(1)

History

(3)

HIV

(2)

Holy Ghost Congress

(1)

Honduras

(1)

Hwasong-15 Missile.

(1)

IMO State

(1)

India

(10)

Indonesia

(1)

Inec

(3)

Info

(3)

Insurgency

(2)

International Amnesty

(1)

IPOB

(1)

Iran

(2)

Iraq

(2)

ISIS

(1)

Israel

(10)

Italy

(3)

Jailbreak

(1)

JAMB

(2)

Japan

(1)

Jerusalem

(2)

Jesus

(1)

Job Opportunities

(1)

Jonathan

(1)

Kabul

(1)

Kano

(1)

Kashim Shittima

(1)

Kenya

(4)

Kenyatta

(1)

Kidnapping

(1)

King Michael 1

(1)

Kiss Daniel

(1)

kogi

(1)

Kogi State

(1)

KSU

(1)

Kwara

(2)

Labour

(1)

Law

(1)

Leadership

(1)

Lebanon

(1)

Legal

(22)

Legal Politics

(1)

Leukemia

(1)

Liberia

(2)

Liberia Election

(1)

Libya

(9)

Libya Ambassador

(1)

Local Government

(1)

London

(2)

Madagascar

(1)

Maina Gate

(1)

Manchester

(1)

Manchester United

(1)

Mapoly

(1)

Marina Gate

(1)

Marriage

(9)

May Theresa

(1)

Migrant

(1)

Migrants

(1)

Militants

(1)

Missile

(2)

Missiles

(1)

MOB 2017

(1)

Moral

(3)

Movie

(1)

Mugabe

(1)

Mumbai

(1)

Music

(17)

Myanmar

(1)

N-Power

(1)

NAAT

(2)

Nasarawa

(1)

NASS

(2)

NASU

(2)

National Convention

(11)

NATO

(1)

Navy

(1)

NAVY Shortlist

(1)

NECO

(1)

Networking

(1)

New Delhi

(1)

News

(320)

News politics

(2)

News Nigeria

(3)

News.

(1)

Neymar

(2)

NGF

(1)

Niger Delta.

(1)

Nigeria

(167)

Nigeria Army

(2)

Nigeria Police

(2)

Nigeria.

(3)

Nigerian Army

(1)

NNPC

(1)

NORTH AFRICA

(1)

North Korea

(8)

NY

(1)

NYSC

(5)

Odinga

(1)

Oil

(1)

Okorocha

(1)

Olamide Concert

(1)

Omotola Jalade

(1)

OPEC

(1)

Oscar Pistorius

(1)

Pakistan

(1)

Palestine

(1)

Paris Fund

(1)

Pastor Adeboye

(1)

PDP

(14)

Pension

(1)

Peru

(1)

Philippine

(2)

Philippines

(3)

Poland

(1)

Police

(1)

Politics

(113)

Politics.

(1)

Pope

(1)

Port Harcourt

(1)

Prof Odekunle

(1)

Putin

(1)

Quattara.

(1)

Racism

(1)

Rape

(4)

RCCG

(2)

Real Madrid

(1)

Refugees

(1)

Relationship

(2)

Religion

(4)

Reno Omokri

(1)

Research

(1)

Restructuring

(1)

Rhianna

(1)

Richest President in Africa

(1)

River State

(1)

Robbery

(2)

Rohingya

(1)

Romania

(1)

Russia

(4)

Russia 2018

(1)

Salaries

(1)

Saraki

(2)

Saudi

(1)

Saudi Arabia

(1)

SEC

(1)

SERAP

(1)

Sexual

(2)

Shettima

(1)

Shiites

(1)

Slave Trade

(2)

SLAVERY

(7)

Slavery.

(1)

Somalia

(1)

South Africa

(3)

South Korea

(3)

Spain

(2)

Sport

(47)

Sports

(3)

SSANU

(2)

Stella DamaSusan

(1)

STRIKE

(2)

Students

(2)

Suarez

(1)

Submarine

(1)

Submit

(3)

suicide

(1)

Surgeon

(1)

Switzerland

(1)

Syria

(1)

Technology

(4)

Terror attack

(3)

Terror attacks

(1)

Terrorism

(1)

Terrorist

(2)

Tinubu

(1)

Tithes

(1)

Togo

(2)

Tourism

(1)

Tragedy

(1)

Trump

(12)

Turkey

(3)

Uganda

(1)

UK

(1)

Umuahia Explosion

(1)

UN

(6)

USA

(26)

Utako Ultra-Modern Market

(1)

Vacancies

(3)

Venezuela

(2)

Video

(2)

War

(1)

War Crime

(1)

Wike

(1)

Wizkid

(1)

Xenophobia

(1)

Yahoo

(1)

Yemen

(2)

Yemi Osinbajo

(1)

Yoruba

(1)

Youth

(1)

Youth Empowerment

(3)

Zimbabwe

(6)

Popular Posts

-

Scientists have warned that the more Viagra-type drugs men take, the lower their sexual confidence becomes. This warning was contained ...

-

North Korea defection: Trees planted, trench dug at site By Ray Sanchez, CNN Updated Nov 25, 2017 (CNN) - North Korea has replaced nearly...

-

WAEC Extends Private Candidates Registration Till January The West African Examination Council (WAEC) has extended the closing date f...

-

SEOUL, South Korea – The Latest on tensions over North Korea's nuclear and missile programs (all times local): 9 p.m. NATO's...

-

The Minister of Information and Culture, Alhaji Lai Mohammed, has said the Peoples Democratic Party is now rebranding itself with the stol...

Powered by Blogger.