It’s do-or-die! Trafficked Nigerians’ route to slavery, deaths in Libya, Mediterranean

It’s do-or-die! Trafficked Nigerians’ route to slavery, deaths in Libya, Mediterranean

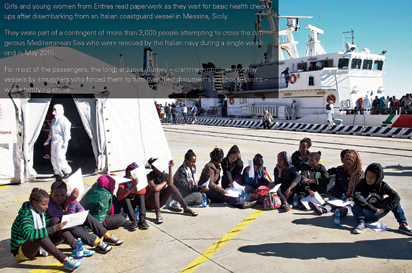

Almost one month after 26 women and girls, believed to be Nigerians, were allegedly murdered while attempting to cross the Mediterranean, the news has continued to send shock waves across the country. The news was swiftly followed by the report that hundreds of Nigerians, among many other trafficked Africans, stranded in Libya on their way to Europe, are being traded as slaves.

The bodies of the women were brought to the southern Italian port of Salerno by the Spanish ship Cantabria on November 5, and prosecutors opened an investigation over suspicions that the victims, some as young as 14, may have been abused and killed.

The bodies were recovered by Cantabria, which works as part of the EU’s Sophia anti-trafficking operation, from two separate shipwrecks – 23 from one and three from the other. 53 people are believed to be missing.

Two men, named as Al Mabrouc Wisam Harar, from Libya, and Egyptian, Mohamed Ali Al Bouzid, are believed to have skippered one of the boats. They were identified by survivors who were among the 375 brought to Salerno by Cantabria.

The two men are accused of organising and trafficking at least 150 people on the two sunken boats, but prosecutors have not made a direct link between the two men and the women’s deaths, said Rosa Maria Falasca, chief of staff at Salerno’s prefecture.

The prefect of Salerno, Salvatore Malfi, told the Italian said the women had been travelling alongside men and when the vessels sank, “unfortunately, the women suffered the worst of it”.

But in response to concerns that the women were being trafficked for sex trade, he added: “Sex trafficking routes are different, with different dynamics used. Loading women on to a boat is too risky for the traffickers, as they could risk losing all of their ‘goods’ – as they like to call them – in one fell swoop.”

Marco Rotunno, an Italy spokesman for the UN refugee agency (UNHCR), said his colleagues were at the port in Salerno when the bodies were brought in.

“It was a very tough experience,” he said. “One lady from Nigeria lost all her three children.”

He added that 90% of migrant women arrive with bruises and other signs of violence.

“It’s very rare to find a woman who hasn’t been abused, only in exceptional cases, maybe when they are travelling with their husband. But also women travelling alone with their children have been abused.”

Most of the survivors were either Nigerian or from other sub-Saharan countries including Ghana, Sudan and Senegal.

The survivors were among over 2,560 migrants saved over four days. People still continue to attempt the crossing despite a pact between Italy and Libya to stem the flow, which led to a drop in arrivals by almost 70% since the summer, according to figures released by Italy’s interior ministry.

Back home in Nigeria and while the identities of the 26 deceased girls have not been disclosed, many parents, whose daughters have travelled to Europe in search of better life, have been gripped by apprehension. Some of the parents do not even know that their daughters, under the lure of searching for golden fleece, and the false assurances of human traffickers, are out there in the open hoping to cover hundreds of kilometres on the sea to get to Europe. Sadly, as some of the girls escape needless deaths by divine intervention, more are struggling to put themselves in the way of harm and death, all in the hope of finding greener pasture. The questions begging for answers are legion. How many times has the tragedy of this nature occurred this year alone? And how many times will it occur before the close of the year?

Abike Dabiri-Erewa, Senior Special Adviser to the President on Foreign Affairs and Diaspora, has, in the meantime, offered some words of assurance as she promised that Nigeria will investigate the 26 girls’ death at the highest diplomatic level. But the announcement by the National Agency for the Prohibition of Traffic in Persons and Other Related Matters, NAPTIP, that it has uncovered about 300 illegal routes in Katsina alone used by human traffickers to ferry their victims out of the country may have underscored the enormity of the problem. UNICEF, on its part, confirmed that there is one route for victims being trafficked from Africa and the Middle East to Europe which, according to the global body, has many tributaries.

Risky route taken by desperate people

“It (route) carries children and women from the hinterlands of Africa and the Middle East, across the Sahara to the Mediterranean Sea in Libya”, a UNICEF report said.

“Every day, thousands travel this route with the hope of reaching safety in Europe. They flee war, violence and poverty. They endure exploitation, abuse, violence and detention. Thousands die. It is not only a risky route taken by desperate people, but also a billion-dollar business route controlled by criminal networks. It is called the Central Mediterranean Migration Route. It is among the deadliest journeys in the world for children. A lack of safe and legal alternatives means they have no option but to use it.

“In 2016, over 181,000 migrants “ including more than 25,800 unaccompanied children “ put their lives in the hands of smugglers to reach Italy.

“The most dangerous part of the route is a 1,000-kilometre journey from the southern border of Libya’s desert to its Mediterranean Coast combined with the 500-kilometre sea passage to Sicily. Last year (2015), 4,579 people died making the crossing or 1 in every 40 of those who made the attempt. It is estimated that at least 700 children were among the dead.

“In Libya, security is precarious, living conditions are hard and violence is commonplace. The country is riven by conflicts as militias continue to fight with each other or with government forces. Different regions are controlled by conflicting militias who make their own rules, control border crossings and detain migrants for exploitation.

“On every step of this dangerous journey, refugees and migrants are easy prey. Children are the most vulnerable”.

UNICEF staff on the ground working with children on this route claimed to have heard and documented many cases over many years of this abuse. “UNICEF works in the countries of origin, transit and destination protecting children from violence, helping them get an education and meeting their basic needs. To build on this work and to further gauge what was happening to migrant children and women who were making this journey, UNICEF’s Libya Country Office commissioned a needs assessment survey in 2016″, the body said.

This gave the global body a window into the scale of the challenge.

The final sample comprised 122 participants, including 82 women and 40 children. The migrant children interviewed for the study represented 11 nationalities. Some of the child interviewees were born in Libya during their mothers’ migration journeys. Among the 40 children interviewed, 25 were boys and 15 were girls between the ages of 10 and 17 years old.

The survey was conducted on the ground by a UNICEF partner, the International Organization for Cooperation and Emergency Aid (IOCEA), with support from Feinstein International Center at Tufts University. The assessment also incorporated interviews with government officials and local non-governmental organizations (NGOs).

Survey of a journey

Though the UNICEF survey’s scope, according to the body, was affected by security restraints and lack of access to militia-run prisons, it still provides important insights into the appalling situation women and children face as they journey along this trail.

“This child alert is not only based on this survey but also on our wider programme experience in North Africa and with children in Italy, and the stories and testimony our staff on the ground have heard countless times from very vulnerable children and adolescents”, UNICEF stated.

‘Pay as you go’ arrangements

Three quarters of the migrant children interviewed reportedly said they had experienced violence, harassment or aggression at the hands of adults. Nearly half the women interviewed reported suffering sexual violence or abuse during the journey. Most children and women indicated that they had to rely on smugglers leaving many in debt under ‘pay as you go’ arrangements and vulnerable to abuse, abduction and trafficking. Most of the children reported verbal or emotional abuse, while about half had suffered beating or other physical abuse. Girls reported a higher incidence of abuse than boys. Several migrant children also said they did not have access to adequate food while on the way to Libya. Women held in detention centres in western Libya, accessed by UNICEF, reported harsh conditions such as poor nutrition and sanitation, significant overcrowding and a lack of access to health care and legal assistance. Most of the children and women said they had expected to spend extended periods working in Libya to pay for the next leg of the journey – either back to their home countries or to destinations in Europe. Although most of the married women (representing three quarters of those interviewed) brought at least one child with them, more children were left behind.

Sexual violence, extortion and abduction

Children and women making the journey, according to UNICEF, are forced to live in the shadows, unprotected, reliant on smugglers and preyed upon by traffickers.

Transport used by women and children interviewed in the survey were mainly trucks, taxis or private cars. About one third indicated that they had travelled long distances on foot or by motorcycle, boat or animals.

Travel through the desert usually required traversing rough sand roads while exposed to heat, cold and dust. Nearly one third of the women interviewed reported that they had experienced fatigue, disease, insufficient access to food and water, lack of funds, gang robbery, arrest by local authorities and imprisonment.

Children also said they did not have access to adequate food while on the journey.

The primary hazards encountered include sexual violence, extortion and abduction. Nearly half the women and children interviewed had experienced sexual abuse during migration – often multiple times and in multiple locations.

Women and children were often arrested at the border where they experienced abuse, extortion and gender-based violence.

Sexual violence was widespread and systemic at crossings and checkpoints. Men were often threatened or killed if they intervened to prevent sexual violence, and women were often expected to provide sexual services or cash in exchange for crossing the Libyan border.

More than one third of the women and children interviewed said their assailants wore uniforms or appeared to be associated with military and other armed forces. These violations usually occurred at security checkpoints within cities or along roadways.

Three quarters of child participants in the study said they had experienced harassment, aggression or violence by adults. Most of the child respondents had suffered verbal or emotional abuse, while about half experienced beating or other physical abuse.

Girls reported a higher incidence of abuse than boys.

Most of the women and children who suffered such abuse did not report it to the authorities. Many participants cited their fear of

being deported or placed in detention centres, and their feelings of shame and dishonour, as reasons not to report sexual violence.

The abuse reported by the children took place in several different contexts, with no definitive trends emerging. About half reported abuse that took place at some point along the journey or at a border crossing.

Approximately one third indicated they had been abused in Libya. A large majority of these children did not answer when asked who had abused them. A few children said they had been abused by people who appeared to be in uniform or associated with military and other armed forces, and several others said that strangers had victimized them.

Contraception injections

Many refugee and migrant women and girls were prepared for this possibility and took precautions against it, depending on the routes they planned to travel. Some women and girls from Eritrea, Ethiopia and Somalia who passed through Khartoum, Sudan, got contraception injections and brought emergency contraception with them on the journey.

Migrant women and children generally tried to travel together for safety reasons but would often be separated. Many women and children also travelled with men to increase their overall security.

Despite these efforts, guards often separated men, women and children from each other, once they arrived at detention centres.

Although it was rarely discussed, men and boys also experienced various forms of sexual violence.

“It is unclear from the survey how many of the 40 children interviewed had arrived unaccompanied in Libya. Almost half the children stated that they arrived with friends, suggesting that they may have arrived with other children. The other half reported that they arrived with parents or relatives”, UNICEF said.

“Estimating the number of unaccompanied children in Libya is difficult. Of the 256,000 migrants estimated to be in Libya, 23,000 are children (9 per cent). One third is believed to be unaccompanied.

“However, the International Organization for Migration believed the actual figure is three times higher. The number of unaccompanied children who arrived in Italy in 2016 – more than 25,800, or three times the number believed to be in Libya – is, in itself, a clear indication of this.

Ninety-two per cent of all children who arrived in Italy last year were unaccompanied, in contrast with the number of children in Libya who are unaccompanied”.

34 detention centres

Unaccompanied children, according to the global body, are especially vulnerable to all forms of violence, abuse and exploitation, including human trafficking.

“They often have no choice but to beg for food and rarely have access to physical or mental health care”, it stated. An estimated 34 detention centres were said to have been identified in Libya. The Libyan Government Department for Combatting Illegal Migration runs 24 detention centres. They hold between 4,000 and 7,000 detainees. Armed groups hold migrants in an unknown number of unofficial detention centres.

The international community, including UNICEF, only has access to fewer than half of government-run detention centres. Women interviewed reported harsh conditions with detainees suffering from the intense heat in the summer and extreme cold in the winter. They were generally not provided adequate clothes or blankets.

The women also reported a lack of food, confirming reports that inmates were significantly undernourished as the quantity and quality of available food were substandard.

The majority of women in the detention centres also reported verbal and physical violence perpetrated by the predominantly male guards.

Children did not receive any preferential treatment and were often placed in cells together with adult detainees, which increased the risk of abuse. Some observers also reported abandoned migrant children in detention centres and hospitals.

The survey confirmed that sanitation conditions were substandard and the centres were, worryingly overcrowded, increasing the likelihood of the spread of infectious diseases. This was compounded by the fact that health-care services were not available, leaving women and girls unable to access feminine hygiene products or medicines. It was estimated that 20 per cent of the detainees were women.

The detention centres often had as many as 20 migrants crammed into cells not larger than two square metres for long periods of time. This resulted in significant adverse health outcomes including the loss of hearing and sight, and extremely challenging psychological challenges.

Living hellholes

The militia-run detention centres were no more than forced labour camps, farms, warehouses and makeshift prisons run by armed groups. For the thousands of migrant women and children incarcerated, they were living hellholes where people were held for months at a time without any form of due process, in squalid, cramped conditions. Serious violations, including allegations of violence and brutality, were commonplace.

UNICEF did not have access to these centres for security reasons, but reports by the United Nations Support Mission in Libya and the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights painted a systematic pattern of human rights abuses.

The militias developed their own detention centres because they could profit from migrants who wished to pass through certain areas. Each militia typically operates its own centre, detaining migrants on the perceived grounds that they bring disease, engage in prostitution and are criminals or mercenaries.

A report by the United Nations Support Mission in Libya revealed high levels of violence with many migrants including children receiving punishment, including torture, for no discernible reason.

Migrants were at a loss for words when attempting to explain why the torture or punishment was taking place.

Migrants were rarely addressed by name but instead were referred to using dehumanizing terms. Sub-Saharan Africans were generally treated much worse than other migrants from Egypt, the Gaza Strip or the Syrian Arab Republic.

Each woman, child pays $1, 200 to smugglers

When asked whether they paid anyone to help them migrate, nearly all the children surveyed indicated they had paid smugglers. Smugglers charged the women and children between US$200 and $1,200 each for the journey, though it was unclear whether the children had made the payment themselves.

In addition, about three quarters of the children reported that someone else helped them along the journey. Almost all those who had received additional assistance got it from family, neighbours or other relatives. Several children also reported that police or other government officials helped them at some point on the journey.

Additional $650 fee

Almost all the women interviewed indicated they had paid a smuggler at the beginning of their journey to reach Libya, after which it was expected they would have to work in transit to raise necessary funds to make the next leg of the journey to Europe.

The women and children reported that they needed additional funds to cover supplies on the journey including food and other basic needs. Nearly 75 per cent of participants borrowed on average US$650 from family, friends or neighbours to cover these costs.

Some interviewees reported abusive treatment by smugglers and said they were always fearful when moved from one location to another, then handed off to a different smuggler they did not know.

Militias also control or exploit ‘connection houses’ where migrants are transferred between smugglers. Smugglers have also been known to take migrants from detention centres to these connection houses where they are often forced to work for an undetermined period based on the smugglers’ demands.

Recruitment in Nigeria

The link between smuggling and trafficking on the route through Libya, according to the UNICEF report, is unmistakable.

“Broadly speaking, smugglers charge people fees to help them cross borders and move through countries by illegal means – it is a business transaction used by people everywhere in the world to overcome barriers that prevent them from seeking safety, protection and new opportunities. Traffickers, in contrast with smugglers, will in addition exploit the people they are transporting, either during the journey or at the destination”, the report said.

“Although very little information about human trafficking was gathered through the IOCEA interviews, other research confirms that Libya is a major transit hub for women being trafficked to Europe for sex. Trafficked Nigerian girls are being sent to Europe on the same route that the smugglers use.

“Nigerian criminal groups typically ‘offer’ victims an irregular migration package to Europe for an estimated 50,000 to 70,000 Nigerian naira (roughly 250 euros) during the recruitment in Nigeria. Such a package promises land, sea or air transportation, making use of counterfeit documents or other means. The person accepts the price with the intention of paying it back by working in Europe.

“Once at destination, the debt is converted into 50,000 to 70,000 euros to be paid in the form of forced prostitution for a period that could last up to three years or longer”.

According to the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, when foreigners are trafficked, the human-trafficking flows broadly follow the migratory patterns. Some migrants are more vulnerable than others, such as those from countries with a high level of organized crime or from countries affected by conflicts.

Increasingly difficult crossing

A survey of migrants and refugees in Italy by the International Organization for Migration in Italy, between October and November 2016 revealed that 78 per cent of children answered ‘yes’ to at least one of the trafficking and other exploitative practices indicators in relation to their own experience.

According to the United Nations Office on Drugs and

Crime, Libya did not have provisions for a specific trafficking in persons’ offence. In addition, the sea crossing from Libya is becoming increasingly difficult, with the European Union expanding its support to the Libyan authorities, including the coastguard. Along with the on-going conflict there, the lack of a codified trafficking offence will continue to make women and children attempting to reach Europe reliant on smugglers and some even knowingly on traffickers. This will make future improvements unlikely, at least in the short term.

Massive people smuggling operation

There is no let-up in the number of children and women, according to UNICEF, forced to make the journey to Italy.

“It has become a massive people smuggling operation, which has grown out of control for the lack of safe and alternative migration systems. It exploits porous and corrupt border security. In January 2017, the height of winter, 4,463 people had to rely on smugglers for the passage to Italy. In the last week of January alone, a staggering 1,852 people made the dangerous crossing, eight times higher than the same week in the previous year”, the body stressed.

“The number of those dying during the crossing via the Central Mediterranean Route is climbing too. An estimated 228 deaths in all are reported so far this year “ 1 in 21 migrants in January, compared to 1 in 24 in December 2016, and 1 in 41 for the entire year 2016. UNICEF estimates that 40 children died in January alone.

“The Central Mediterranean Route sparse Saharan terrain and the vacuum created by the Libyan conflict. It is time to stop the exploitation, abuse, and death of women and children on this route of misery. Women and children deserve to be protected from violence, exploitation and abuse along their journey. “They should not have to put their lives in the hands of smugglers.They should be afforded safe and legal pathways to a better life”.

Fast facts

- As of September 2016, an estimated 256,000 migrants have been identified in Libya, out of which 28,031 are women (11 per cent) and 23,102 are children (9 per cent), with a third of this group including unaccompanied children. The real figures are believed to be at least three times higher.

- Of the 181,436 arrivals in Italy in 2016 via the Central Mediterranean Route, 28,223 or nearly 16 per cent were children.

- Nine out of ten children who crossed the Mediterranean last year were unaccompanied. A total of 25,846 children made the crossing, which is double the previous year.

- An estimated 4,579 people died crossing the Mediterranean between Libya and Italy last year alone.

We practically walked to Libya — Pati, 16, from Nigeria

“The journey was hard, because we had to walk, no cars, without any drinking water. We crossed the desert walking, it took almost two weeks. Sometimes we had to walk a full day without drinking any water – sometimes we went two days without water – before we arrived in Libya. Without enough water, without enough food”.

They treat us like chickens — Jon, an unaccompanied child from Nigeria in detention in Libya

“In Nigeria, there is Boko Haram, there is death. I did not want to die.

I was afraid. My journey from Nigeria to Libya was horrible and dangerous. Only God saved me in the desert, no food, no water, nothing. The guy who was sitting next to me on the trip died.

And once one dies in the desert, they throw away the body and that’s it. I have been here [in the detention centre] for seven months. Here they treat us like chickens. They beat us; they do not give us good water and good food. They harass us. So many people are dying here, dying from disease”.

I did not know journey was this dangerous — Aza, Kamis’ mother

“I decided to leave Nigeria because there was no work. I wanted to work and help my children. I did not know the journey would be so dangerous. I realized it when we were approaching the sea and I thought that this was not going to be so easy. They did not tell me the truth.

They did not tell me the risks involved or the difficulties I would face. It all became a reality for me when I saw the situation. The sea that expanded right before my eyes. But once we were at sea we could not turn back. I paid US$1,400 for that trip. If I had decided not to leave, no one would have returned the money to me. I have done all this for my children and for their future, and I did not want to lose them”.

I thought I would be a doctor in Italy but ended in Libyan dungeon — Kamis, 9, from Nigeria

“My mother tried to bring us to Libya because of the difficult situation in Nigeria. We had no money because my mother was not working. We came from Nigeria to Libya via Agadez, Niger. A man died in our car. So we were sad. The men who pushed us on the boat told us to look at the stars. The boat was in the middle of the sea and everybody was crying. The wind was moving our boat, so everybody was shouting. Everybody was crying.

When we saw a small ship, we shouted: ‘Please come and rescue us.’ They rescued us and took us to dry land. Then, we were moved to Sabratha detention centre where we stayed for five months. There was no food and no water. In Sabratha, they used to beat us every day. There was no food there either. A little baby was sick but there was no doctor on-site to care for her. That place was very sad. There’s nothing there. They used to beat us every day. They beat babies, children and adults. One woman in that place was pregnant. She wanted to deliver the baby. When the child was born, there was no hot water. Instead, they used salt water to take care of the baby.

What do I want to do when I grow up? I want to be a doctor in my future because I like medicine. Before we left Nigeria, I told my mother, ‘I want to be a doctor.’ My mother answered, ‘Don’t worry. When we reach Italy, you will be a doctor’”.

Unknown Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetuer adipiscing elit, sed diam nonummy nibh euismod tincidunt ut laoreet dolore magna aliquam erat volutpat.

Labels

#End SAR

(1)

#End SARS

(5)

2019

(1)

9/11

(1)

Abacha Loot

(1)

Abuja

(1)

Accident

(3)

Adewunmi

(1)

AfDB

(1)

Afghanistan

(2)

Africa

(6)

African Culture

(1)

Agriculture

(1)

Aisha Buhari

(1)

Ajunwa

(1)

Akwa Ibom

(1)

Anglophone

(1)

Anita Joseph

(1)

APC

(1)

Argentina

(1)

Art

(3)

Article

(24)

Assault

(1)

AU

(2)

Australia

(1)

Australia Parliament

(1)

Babies

(1)

Banking

(1)

Barrack Obama

(1)

Bayelsa

(1)

Bayelsa State

(1)

Bayern Vs PSG

(1)

BBC

(1)

Bello

(1)

Benue State

(4)

Bitcoin

(4)

Bobrisky

(1)

Bokoharam

(1)

Bombing

(1)

Bosnia

(1)

Brazil

(1)

Brexit

(3)

Britain

(1)

BudgIT

(1)

Buhari

(6)

Burna Boy

(1)

Business

(2)

Cameroon

(2)

Catalonia

(1)

CBN

(1)

Champions League Draw

(1)

Charlyboy

(1)

Child Abuse

(1)

Child Rape

(2)

Chile

(1)

China

(9)

China.

(1)

Christmas

(1)

Christmas 🌲

(1)

Cocktail

(1)

Commits Suicide

(1)

Corruption

(2)

Cote d'Ivoire

(1)

Coup

(1)

CPS

(1)

Crime

(5)

Cure

(1)

Cyprus

(1)

Czech Republic

(1)

Daddy Freeze

(3)

Daura

(1)

David

(1)

Disco

(1)

Documentary

(1)

Domestic Violence

(1)

Dr Chris Ngige

(1)

Earthquake

(2)

Economy

(14)

ECOWAS

(1)

EDUCATION

(8)

EFCC

(3)

Eid el-Malud

(1)

Ekiti

(1)

Ekiti State

(3)

Election

(7)

Entertainment

(9)

Enugu

(1)

EU

(3)

Europe

(1)

Export

(1)

Extra- judicial killing

(1)

Fashion

(3)

Fayose

(1)

FBI

(1)

FCSC

(1)

FEC

(1)

Federal Government

(3)

Fela

(1)

FETO

(1)

FIFA

(1)

Fire Accident

(1)

Florida

(1)

Floyd Mayweather

(1)

Food Recipe

(1)

Food Recipes

(3)

Football

(1)

Football News

(2)

France

(1)

Fraud

(2)

FRSC

(1)

Fuel Scarcity

(1)

Fulani Herdsmen

(7)

Fun

(3)

Future Awards Africa Winners

(1)

G- Worldwide

(1)

Gay

(1)

Gaza

(1)

Germany

(5)

Ghana

(1)

Gist

(1)

Gossip

(55)

Gossips

(1)

Guinness World Record

(1)

Hamas

(1)

Health

(50)

Highlight

(1)

History

(3)

HIV

(2)

Holy Ghost Congress

(1)

Honduras

(1)

Hwasong-15 Missile.

(1)

IMO State

(1)

India

(10)

Indonesia

(1)

Inec

(3)

Info

(3)

Insurgency

(2)

International Amnesty

(1)

IPOB

(1)

Iran

(2)

Iraq

(2)

ISIS

(1)

Israel

(10)

Italy

(3)

Jailbreak

(1)

JAMB

(2)

Japan

(1)

Jerusalem

(2)

Jesus

(1)

Job Opportunities

(1)

Jonathan

(1)

Kabul

(1)

Kano

(1)

Kashim Shittima

(1)

Kenya

(4)

Kenyatta

(1)

Kidnapping

(1)

King Michael 1

(1)

Kiss Daniel

(1)

kogi

(1)

Kogi State

(1)

KSU

(1)

Kwara

(2)

Labour

(1)

Law

(1)

Leadership

(1)

Lebanon

(1)

Legal

(22)

Legal Politics

(1)

Leukemia

(1)

Liberia

(2)

Liberia Election

(1)

Libya

(9)

Libya Ambassador

(1)

Local Government

(1)

London

(2)

Madagascar

(1)

Maina Gate

(1)

Manchester

(1)

Manchester United

(1)

Mapoly

(1)

Marina Gate

(1)

Marriage

(9)

May Theresa

(1)

Migrant

(1)

Migrants

(1)

Militants

(1)

Missile

(2)

Missiles

(1)

MOB 2017

(1)

Moral

(3)

Movie

(1)

Mugabe

(1)

Mumbai

(1)

Music

(17)

Myanmar

(1)

N-Power

(1)

NAAT

(2)

Nasarawa

(1)

NASS

(2)

NASU

(2)

National Convention

(11)

NATO

(1)

Navy

(1)

NAVY Shortlist

(1)

NECO

(1)

Networking

(1)

New Delhi

(1)

News

(320)

News politics

(2)

News Nigeria

(3)

News.

(1)

Neymar

(2)

NGF

(1)

Niger Delta.

(1)

Nigeria

(167)

Nigeria Army

(2)

Nigeria Police

(2)

Nigeria.

(3)

Nigerian Army

(1)

NNPC

(1)

NORTH AFRICA

(1)

North Korea

(8)

NY

(1)

NYSC

(5)

Odinga

(1)

Oil

(1)

Okorocha

(1)

Olamide Concert

(1)

Omotola Jalade

(1)

OPEC

(1)

Oscar Pistorius

(1)

Pakistan

(1)

Palestine

(1)

Paris Fund

(1)

Pastor Adeboye

(1)

PDP

(14)

Pension

(1)

Peru

(1)

Philippine

(2)

Philippines

(3)

Poland

(1)

Police

(1)

Politics

(113)

Politics.

(1)

Pope

(1)

Port Harcourt

(1)

Prof Odekunle

(1)

Putin

(1)

Quattara.

(1)

Racism

(1)

Rape

(4)

RCCG

(2)

Real Madrid

(1)

Refugees

(1)

Relationship

(2)

Religion

(4)

Reno Omokri

(1)

Research

(1)

Restructuring

(1)

Rhianna

(1)

Richest President in Africa

(1)

River State

(1)

Robbery

(2)

Rohingya

(1)

Romania

(1)

Russia

(4)

Russia 2018

(1)

Salaries

(1)

Saraki

(2)

Saudi

(1)

Saudi Arabia

(1)

SEC

(1)

SERAP

(1)

Sexual

(2)

Shettima

(1)

Shiites

(1)

Slave Trade

(2)

SLAVERY

(7)

Slavery.

(1)

Somalia

(1)

South Africa

(3)

South Korea

(3)

Spain

(2)

Sport

(47)

Sports

(3)

SSANU

(2)

Stella DamaSusan

(1)

STRIKE

(2)

Students

(2)

Suarez

(1)

Submarine

(1)

Submit

(3)

suicide

(1)

Surgeon

(1)

Switzerland

(1)

Syria

(1)

Technology

(4)

Terror attack

(3)

Terror attacks

(1)

Terrorism

(1)

Terrorist

(2)

Tinubu

(1)

Tithes

(1)

Togo

(2)

Tourism

(1)

Tragedy

(1)

Trump

(12)

Turkey

(3)

Uganda

(1)

UK

(1)

Umuahia Explosion

(1)

UN

(6)

USA

(26)

Utako Ultra-Modern Market

(1)

Vacancies

(3)

Venezuela

(2)

Video

(2)

War

(1)

War Crime

(1)

Wike

(1)

Wizkid

(1)

Xenophobia

(1)

Yahoo

(1)

Yemen

(2)

Yemi Osinbajo

(1)

Yoruba

(1)

Youth

(1)

Youth Empowerment

(3)

Zimbabwe

(6)

Popular Posts

-

Scientists have warned that the more Viagra-type drugs men take, the lower their sexual confidence becomes. This warning was contained ...

-

WAEC Extends Private Candidates Registration Till January The West African Examination Council (WAEC) has extended the closing date f...

-

North Korea defection: Trees planted, trench dug at site By Ray Sanchez, CNN Updated Nov 25, 2017 (CNN) - North Korea has replaced nearly...

-

SEOUL, South Korea – The Latest on tensions over North Korea's nuclear and missile programs (all times local): 9 p.m. NATO's...

-

The Agbalumo Or Udara Cocktail You Have To Try It's the season of the African Star Fruit or Apple, known traditionally as Agbalumo...

Powered by Blogger.